The Light Curve of 2008 TC3

On the night of the 2008 TC3

encounter several observers made long sequences of photometry of the asteroid.

MPC 213 and MPC J47 together have 285 internally consistent photometric

observations (i.e. reduced against the same reference stars) covering more than

66 minutes in total.

In the images of J47 it is obvious that the

asteroid is flashing regularly (i.e. the asteroid is irregular and rotating

quickly, as would be expected for such a small object).

The problem is to calculate the best fit to the

period from the data.

This is a very simple problem to resolve with

an Excel spreadsheet and a little trial and error, even without using

periodicity-fitting routines.

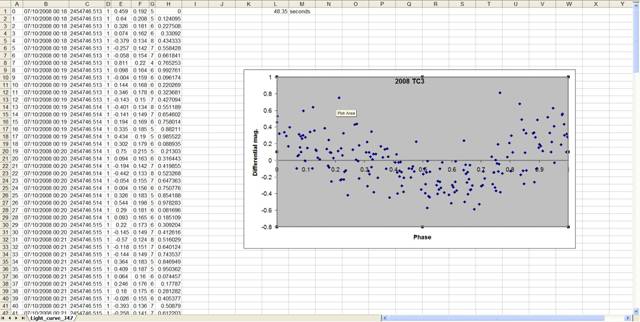

First you remove the trend in the data (2008

TC3 was brightening rapidly) and then you fit the data around a series of trial

periods, as shown below. This plot shows that the data from MPC 213 is a pretty

good fit to a period of 48.35 seconds, with a single maximum and minimum.

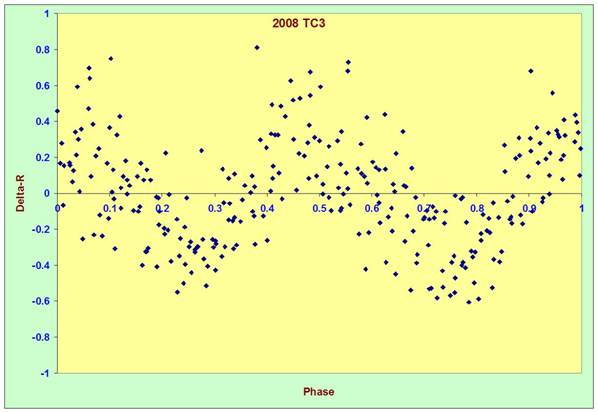

However, when you add in the data from MPC J47,

giving a much longer time base, you see that they are clearly out of phase. In

other words, however good 48.35 seconds looks over a short period of time, it

is not the best fit to the data, although quite close to it.

In fact, for a triaxial figure: that is, an

elongated object, you would expect two maxima and minima per rotation period.

When we try double the period: around 97s, we

find a nice light curve, with two maxima and minima per period. There is some

scatter in the data, but it must be remembered that the signal-to-noise ratio

per point was typically 8, giving a photometric error of around 0.14 magnitudes

on a single observation. In other words, we must expect a considerable scatter in the data.

The data is very sensitive to very small

changes in the trial period. Even a change of 0.05 seconds makes a visible

difference to the fit. By trying different periods we can find the best fit to

the data, reducing its scatter.

The best fit is found for a period of

97.13+/-0.03 seconds. The period is very sensitive to changes and, outside this

range, the fit to the data is clearly not so good.

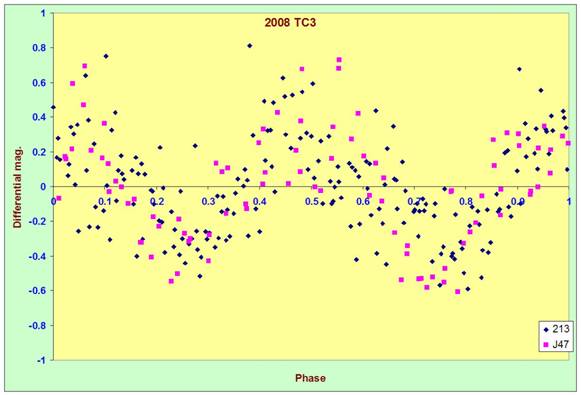

The light curve shows a double maximum, with

amplitudes of 0.6 and 0.8 magnitudes for the two maxima, as shown below.

There are a few outlying points, but these can

be attributed to bad data on a night of occasionally variable conditions. The

data suggest that the asteroid had a strongly elongated shape.

We can look at how well the data from the two

stations fit this period individually. In the next plot data from MPC 213 are

shown in blue and from MPC J47 in magenta. The data agree very well with each

other, showing that they are nicely in phase and show the same amplitude over a

period of more than an hour.

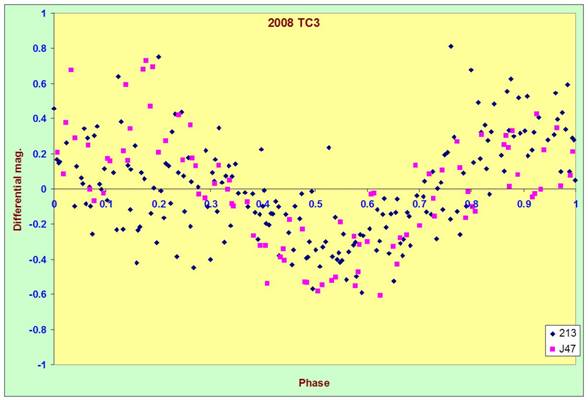

We can also look to see if there is actually a

good fit with a single maximum and minimum per rotation. This would be a period

of one half of 97.13 seconds. The data, fitted around a period of 48.62 seconds

show though that, although from phase 0.4 to 1.0 there is a good fit, the fit

is poor from phase 0 to 0.4 there is strong disagreement: this is what you

would expect from a light curve that shows two maxima and minima with different

amplitudes.

In this case there is clearly not a good

agreement between the two observatories over part of the light curve cycle and

this period of 48.62 seconds can probably be discounted in the light curve.